CSW 65 Webinar Jing Zhang : The actual social status of Chinese women

By WRIC Jing Zhang March 18, 2021

Note: United Nations CSW 65 Webinar – President Jing Zhang of Women’s Rights in China was invited to speak: The actual social status of Chinese women

The actual social status of Chinese women

Although we’re meeting over COVID this year for Women’s History Month, it hasn’t stopped us from focusing our attention onto women’s and girls’ rights there at the UN Commission on the Status of Women via the Internet. Today, we’ll share with you an overview of women’s status in China and the root causes for the severe discrimination against women there, with the hope to deepen and broaden the world’s understanding of women’s rights in China.

The centurial lack of women within the CCP leadership

Within the century since the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Politburo Standing Committee has consisted of men and only men. During its rule over China in the past 72 years, only 6 women in total have made it into the Politburo, and 3 of those were wifes of the General Secretaries or the Premiers: there hasn’t been any woman within the CCP’s leadership who could actually speak out for her sex. This gender imbalance in political participation is one of the main reasons for the deprivation of women’s rights. The making and execution of policies and law have historically been entirely dominated by a few decision-making men. Taking reproduction as an example, we see how the CCP leadership encouraged women to have multiple children in the 1950s, then between the 1970s and 2010s, inhumane measures were taken to enforce birth control and abortion in order to fulfill the One-Child Policy; then in the 2010s, the policy relaxed to a quota of two; and now as we’ve entered the 2nd decade of the 21st century, they are forcefully pushing for women to bear more children for the country. Such control over women’s fertility and the birth and death of babies has been exerted by just the few men within the Politburo.

The women depicted in the CCP’s political propaganda have always looked prime and radiant, exuding confidence and an air of intelligence, living freely and meeting life’s challenges deftly. But the latest data have revealed the truth of women’s lives in China: The Global Gender Gap Report 2020 published by the World Economic Forum ranked China in the 106th place within the 153 countries represented; even some African nations in extreme poverty were ranked higher for women’s status. Xi Jinping cashed in 10 million USD to UN Women in 2015 and received a chance to speak at the opening ceremony of the Global Leaders’ Meeting on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in September that year. And during the few months before that, in order to silence the voices of dissent within China, his admin arrested the Feminist Five for just holding up signs against sexual harassment. Women’s rights in China worsen year after year under Xi’s rule, with inequality and discrimination faced by women becoming more and more common and widespread.

Life: WRIC with the feminist organizations protesting in front of the UN in 2015 in support of the Feminist Five. Right: WRIC protesting against the hypocrisy of Xi speaking at UN Women yet oppressing women at home (Photos by WRIC)

Systemification of sexual assault and rape

Although the #MeToo movement did make its way into major Chinese cities over the past few years, but most victims of sexual assault in China have remained silent or could only speak anonymously online as they either couldn’t afford a lawsuit or had been blackmailed into not pursuing one. In March 2020, a blogger known as Stacey in China conducted a questionnaire survey online on sexual offences on women. She received over 45,000 responses over the span of a few days. Over 85% of the respondents admitted that they had been sexually harassed or violated before. Some have even left behind comments in which they shared their experiences of being harassed by male colleagues or bosses; there were also stories of them being fired after filing a case to their senior managers. In a report submitted by Professor Fang Xiangming to the WHO, 11.5% of girls and 9.6% of boys in China had been sexually assaulted before. This amounts to over 20 million children per year.

Jurisprudence researcher Tian Gang had also pointed that at least 21% of women in China had been subject to sexual assault, and 24.7% to marital rape. These are the numbers that the Chinese government allows out. One can only imagine how much bigger the numbers would be in reality.

About 80 million parents in China work in the cities and leave behind their children in the rural areas with their grandparents. These children are often subject to rape by their extended family and other villagers. Often these rapists are the village officials or their kin, meaning that the parents of these children wouldn’t be able to do anything about the crimes. Minors also fall victim to rape by teachers at school. This phenomenon has persisted for years because the government never penalised the offenders. Wang Yu, a Chinese lawyer and the recipient of the 2021 Women of Courage Award, had led a protest in Hainan along with a few other feminist activists against a case of 6 primary schoolgirls being brought to a hotel and raped by their headmaster.

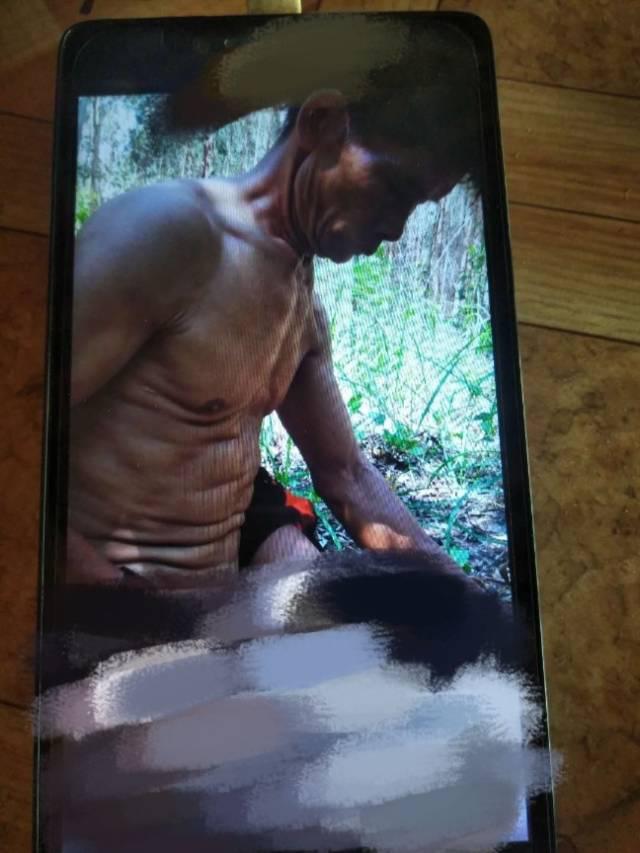

In September 2020, Xu Mouke, a 60-year-oldman in Leizhou City, Zhanjiang, raped an 8-year-old left-behind girl from his neighbor. The girl’s 11-year-old brother took this scene. He passed the photo to his father as evidence. The parents of the girl who were victimized said that they had called the police and accused Xu of sexually assaulting an underage girl. Because there was no evidence, the police did not open the case. (Internet picture)

Feminist activists including Ye Haiyan and Lawyer Wang Yi protesting in front of South Wanning Primary School in 2013 over the 6 pupils raped by the headmaster, holding up a sign saying “Get me if you want sex, leave the kids alone.”( Online)

In an event organized by WRIC to support 10-year-old Annie’s right to go to school, lawyer Wang Yu ( woman) came forward and negotiated with the police about the legality of the activity.(Photos by WRIC)

Sexual assault and rape crimes in China has become systemic over the years and across all layers of society as well as a spectrum of establishments.

I have myself witnessed female inmates being raped by prison officers back in the 1980s in Guizhou. They were often taken away by officers for ‘independent work’, and when they returned to the prison cell they were extremely spent and would only cower and weep in a corner. Anyone who spoke among themselves about it or who whistle-blew would be publicly shamed or punished. The recently surfaced case of the Ma sisters in Shenyang is another proof of the systemic inprison rape in China that the authorities do not even bother to hide anymore.

The systemic assault on women in any form of captivity is also readily found in peripheral China. The Uyghur women among the 2 million captives in the concentration camps in Xinjiang were not only forced to sing and dance for the Han managers, but also gang-raped by them. Many escapees from the camps have revealed to foreign media their experience and what they had witnessed. Tursunay Ziawudan told the press that during her 9 months in the camp, she was repeatedly raped by a man in a suit and face mask inside of a pitch-dark room without any surveillance cameras installed. The women in the camps would be taken away each night and raped by one or multiple masked men. She had herself been tortured three times by two to three men before they began to gang-rape her regularly. She considered herself extremely lucky to have been able to escape and vocalise the truth — most other women there could not even dream of the opportunity.

Within the Uyghur communities, after the men in the family had been kicked into the concentration camps, the emptied-out spot at home would be filled by a Han official. This is part of the CCP’s ‘matchmaking’ schemes. Over the years, the CCP has sent over 1 million Han men into Uyghur homes for surveillance.

Right: An Uyghur exile in Taiwan, in tears, on her experience of being sexually assaulted at an interview by CTS Taiwan in 2019 (Screencapped from CTS)

And down in Hong Kong, many female protesters and detainees had been subject to different kinds of sexual offences and even rape by the police officers. A prominent case is of a 15-year-old girl Christy Chan Yin-lam who was found dead naked in an inland harbour in September 2019 at the peak of the Anti-Extradition protests. She was known to have been a pro-democracy supporter. And the pathology expert who testified at the coroner’s inquest had expressed that the condition in which she was found was extremely unnatural. Her two lungs weighed differently, which was atypical of a drowning victim; and a prototypical yet crucial test that could’ve been done to constrain the potential causes of death was not done by the pathologist who carried out the autopsy. The case received an open verdict from the coroner’s jury due to insufficient evidence to confidently land on any other available causes of death, and her case has remained a mystery since. There were yet many more young female protesters being groped by the police during arrest operations. Some incidents had been captured on live streams, but yet more would have happened in places where they couldn’t have been documented.

A young woman at an Anti-Ex tradition protest in Hong Kong being pinned down and groped repeatedly by police officers. (Internet image)

Incidents of sexual violence against female protesters by the Hong Kong police.

Artwork in tribute to Christy Chan Yin-lam, the 15-year-old girl whose cause of death remains undetermined (Image credit back to its original artist)

Workplace discrimination

Over the past 40 years, the economic growth in China has exacerbated the gender income gap in the country. A 2020 report by a human resources platform revealed that women earn only 70% of what men do in the cities in the five years leading up to 2020; the income gap became wider the longer they were employed. Discrimination against women is found through from university admissions to employment. According to Human Rights Watch, 11% of vacancies in the public service were open to men only in 2020; this number was 19% back in 2018 and 2019. WRIC has received reports from women on being discriminated against at the workplace: applicants for posts in journalism have been asked to sign off to terms such as not to have children within the first 5 years of employment on their contracts. Inequality is even worse in the rural areas: for the same amount of physical labour, women are paid 20% less than men.

According to an investigation done in 18 provinces in China by the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, 98% of the female workers in manufacturing in the rural areas do not have any health family planning insurance; 72% of them are unprotected by any health insurance, a shocking 29.6% of them have even been asked to work during pregnancy.

State-owned All-China Women’s Federation have published data on the female employers’ perception of the gender discrimination they experience: 22% of them expressed that there is severe discrimination; 59% expressed that there is a moderate level of discrimination. A civil society-led investigation on the condition of the current workplace for women in 2020 found that 27% of them had been told that certain posts are reserved for a certain gender only; 58.25% of women had been asked questions on their marital status or on family planning during job interviews; and 6.39% had been demoted or moved posts during family planning. Most of these data are officially published, meaning that the reality could be way worse.

Discrimination not only occurs in the workplace, but it also appears in any corner of society at any time. The judge’s decision is also inseparable from discrimination and injustice. A “blackmail case” in Jiangsu from March 2021 is jaw-dropping, but not uncommon.

A scandalous case of blackmailing occurred in Jiangsu in March 2021. A single woman had sexual relations with nine officials in five years. The judge sentenced the woman to 13 years in prison and confiscated her 3.726 million yuan of “extortion” from nine men and a fine of 5 million yuan. In this case, The government benefited 8.7 million yuan from the girl. Nine married men and the high officer all became victims.

The PUA culture is deemed as extreme misogyny by the West and yet when it found the right soil in China it proliferated as a full-blown industry. The leading PUA company in China had over 400 employees in 2017 and over 100,000 subscribed members. Another one, which runs an online course, had 2 million subscribers in 2018. These courses teach men how to inflict psychological pain on women, seduce and set up rapes charge up to a few tens of thousands of Chinese yuans for tuition.

‘Naked loans’ is an industry. Loan companies collude with the mafias and target college and even high school girls nationwide for high-interest transactions. Many students came from the rural area and couldn’t afford the high living cost in the cities, and as governmental funding is non-existent, they had to turn to the devil’s deals. The girls need to send over a selfie photo or video of themselves naked holding out their ID cards in some form of erotic pose as collateral when borrowing. If they couldn’t pay off the loans and the interest by the due date, the company would publicise their nudes and personal communications. Some girls could even be forced into prostitution to pay off their loans. Some have taken their own lives over this. WRIC received an email back three years ago in which over 100 girls’ stories of being sexually abused had been documented, along with their nudes. We haven’t been able to publicise these stories as we aren’t able to guarantee protection for the girls given the collusion between the police and the mafias in China.

Life: A salesman at a pop-up stall selling ‘naked loan’ plans outside of a university in Wuhan in 2016. (Online photo)

Right: Selfie of a naked female loaner holding up her ID card being used as collateral for the loan. (Photo by WRIC)

Large-scale trafficking of women

In the 2020 Trafficking in Persons Report published by the US State Department on 25th June, China was ranked the third worst. This is the fourth time that China has made it onto the list since 2017. Since the Chinese government had never submitted any law enforcement data, and the crime data reported were heavily hedged, it’s difficult to evaluate the reality of the situation in China. What could be found about the trafficking of women in China on the UN’s website is from 10 years ago, and the data came from the Chinese authorities themselves. (http://kidnap.bz.cn/2019/7477.html)

Women aren’t trafficked just within China, but transnationally as well. WRIC has received many alerts of illegal prostitutes from China in the US. They work all year around and may take up to a few tens of clients per day, even that barely covers the stowaway cost. Some have been rescued with help from the US police, and as we hoped that they could stand as witnesses against the traffickers at court after they had settled into their new lives on their V visa, they had not been able to due to fear of retribution at their families back in China.

The One-Child Policy had skewed the gender ratio of China, it created a phenomenon of at least 30 million bachelors without a match today. These men resorted to buying themselves a wife from South East Asia to bear them children. According to an incomplete survey, there were over 100 thousand ‘Vietnamese brides’ in China in 2015; less than half of them were legally married to a man, most of them lived in extreme poverty in rural villages and went about without an ID. Allegations of disappearances and deaths of these South East Asian brides are not uncommon, but there have never been any official numbers.

The public sign said: Buy a Vietnamese virgin bride for 200 thousand yuan (30,700USD). (Internet picture)

Domestic violence and suicide as a norm

According to the data from the state-owned All-China Women’s Federation, domestic violence occurred in 25% of the 270 million families in China in 2019; 157 thousand females commit suicide each year, 60% of those were caused by domestic abuse. One woman is abused at home every 7.4 seconds on average; the victims endure an average of 35 abuses before they’d call the police. Death by domestic violence makes up over 40% of foul play for women. The abusers are mostly male. A semi-state-owned women’s rights organisation has also pointed out that between 1 March 2016 and 31 October 2017, 533 cases of death by domestic violence had been recorded; these involved 635 deaths including also children, meaning that at least one person dies from domestic abuse each day on average, and she is likely a woman.

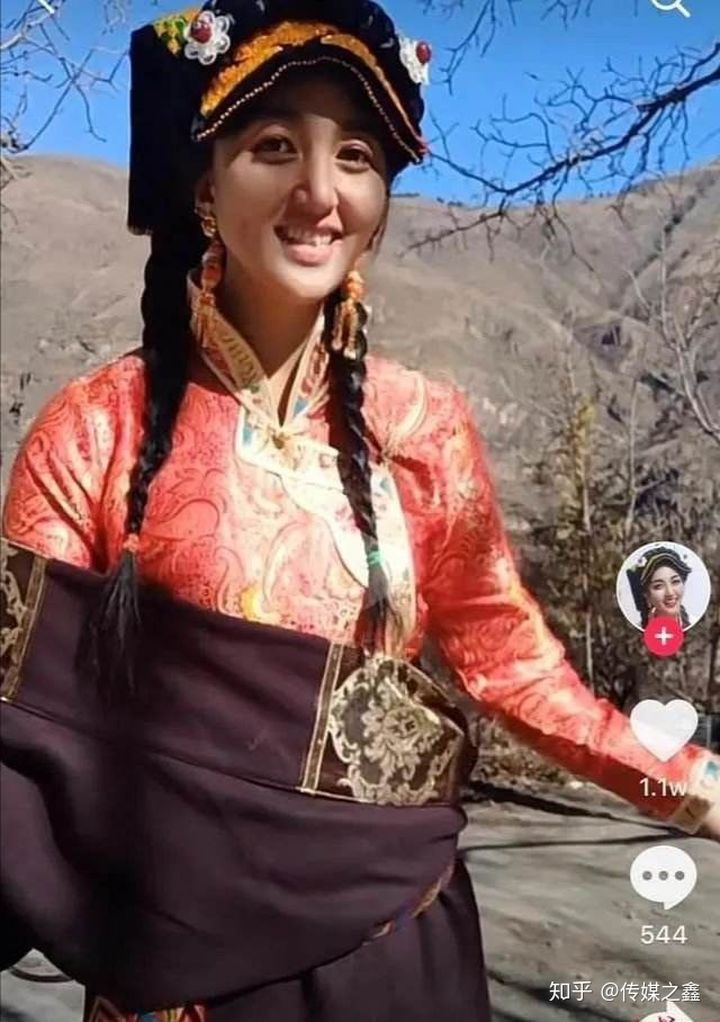

In light of the high divorce rate in China, a 30-day cooling-off period has been legislated and enforced since 2020. During these 30 days, victims of domestic abuse could be subject to yet more violence and threats. A young Tibetan woman in Sichuan was repeatedly attacked by her husband who habitually splashed gasoline onto her, with all her calls for help ignored by both the local law enforcers and the court, she was eventually burned to death after two weeks.

A picture of the late Tibetan victim of domestic abuse.(Internet image)

China was once a country in which the female suicide rate was higher than that for male: rural women are 60% more likely to kill herself than men, while the global average finds that men are 25% more likely to commit suicide than women. Academics think that the movement of rural women to the cities had kept women away from the lethal herbicides with which they could use to kill themselves. However, as the Chinese government began their operations to chase rural workers back home as cities began to saturate, these figures are likely to rise again. The Chinese authorities are unlikely to take actions as they continue to push for a high rate of economic growth at the expense of the workers’ basic human rights. Against this backdrop, rural women and children will suffer the most.

Recent years have seen the Chinese government’s implicit plan to force rural-originated workers away from the cities as the urban areas got overburdened and as the government had finished milking out all the cheap manpower they could get from these workers. In 2017, the Beijing authorities began the most radical operation to force rural-originated workers back home. The mayor flattened an entire area that used to house over 10,000 workers and the families whom he deemed ‘lowlives’ overnight by claiming that there was a fire. From then on, there were no more rural-originated workers in Beijing, but only the urban population and the awe-inspiring skyscrapers that these workers had built.

With COVID-19 taking a serious toll on the country’s economy and with local authorities using epidemic control as an excuse to banish rural-originated workers, hundreds of millions of them will now return to the barren lands from which they gave their all to build a life away. What awaits the middle-aged women that return into such an environment is unemployment, infertility, discrimination and helplessness, and the old way of life in which they could just end their lives with a mouthful of herbicide, where there would be even less chance for them to access professional support. The Chinese government has ignored the severity of the consequences and has done nothing to prevent women from committing suicide.

The warzone-like ruins of the Da Xing district that used to be home to the rural workers in Beijing. (Photo by Bryan Denton)

Closing remarks:

The systemic sabotage of women by the CCP

Researchers have distilled the factors behind the high female suicide rates into 3 C’s: Communist, Confucius, and Commercial. In fact, the last C can’t be the main cause for suicide as the Chinese people are rather accustomed to poverty, and poverty-driven suicide attempts have been extremely rare. The real driver for the high rural female suicide rate is the 40-year-long draconian one-child policy along with a series of related legislation, which regressed society back into the malfunctional system of the past and led to the further degradation of what little remained of women’s rights in China.

Within the little-known Chinese Museum of Women and Children in Beijing, none of the displays were the drugs or tools used to control women’s fertility, nor are there any numbers or text showing the harm inflicted on the hundreds of millions of women subject to the cruel fertility policies devised by the government, nor anything about the forty million aborted babies as mothers were coerced to comply to the one-child policy. 40 years of the largest forcible birth control operation known to man had disappeared on the land of China, just like how children born in the 90s in China had never heard about the Tiananmen Massacre. All this reflects the ironic success of the CCP at covering up history and shutting up mouths forever.

Since Xi Jinping began his rule, women were put back into the home as just a wife and a child bearer. The status of women in society described in ancient literature that even Mao had scorned at has been brought back to life. In the CCP’s eye, the diminishment of women helps consolidate their rule. Xi’s oppression of women who would speak out against it paints a grim future for feminism in China, one in which patriarchy prevails and grows ever stronger and women’s rights and living space shrivel into nothing.

***********************

About Jing Zhang:

Jing Zhang is the youngest member of the Chinese Democracy Wall movement in 1979. She wrote the articles criticizing the Chinese government, and she was sentenced to 5 years in prison. After being released, she worked as an editor for a newspaper in Hong Kong. After Hong Kong returned to China in 1997, she came to the United States and continued to work as an editor for Chinese newspapers and continued to advocate for democracy in China.

In 2007, Jing Zhang established the Women’s Rights in China organization, dedicated to fighting for the rights and interests of Chinese women and children and promoting women’s political and social status.