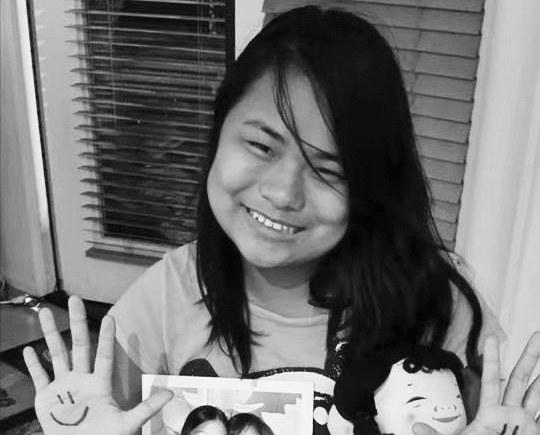

Adoptee Ivy N Maldonado’s Story

Reprinted from Our China Stories Oct 4, 2019

WRIC editor’s note:

The children of the Social Welfare Institute (Orphanage) in Yiwu City, Zhejiang Province, China have the surname “Ni” because “Ni” and “yi” are the same in Yiwu dialect. It is understood that since the Yiwu Social Welfare Institute was approved for foreign-related adoption in July 1994, at least nearly 500 children have been sent to 11 countries including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. Most of the country’s family adoptions are girls, 90% are adopted by Americans, and there are more than 100 disabled children. The characteristics of China’s children’s welfare homes are that the majority of children are girls, followed by disabled children, and boys who are physically and mentally healthy are rare.

In fact, not all children adopted by social welfare institutions in various provinces, cities or counties in China are orphans, especially in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s when family planning was strictly implemented. Later, they were sold to orphanages as collateral and fines. After their identities were cleared, they were allowed to be adopted by foreigners at a high price. Due to the large interest chain involved, many orphanages are still tightly covered up to date. The 80 abandoned infants in the Zhenyuan Welfare Institute in Guizhou revealed around 2005 all have the “Ancient City Series” names, such as Guchenghui, Guchengqian, Guchengmei, and Guchengwei. The ancient city is the old name of Zhenyuan County.

Ivy’s interview

Mar 29, 2019

My name is Ivy and my intro to Our China Stories is not like everybody else’s story. It’s an original, unique, and one-of-a-kind story.

My story is a living testimony of hope and unconditional love. The reason I purposely chose to put my China adoption story out there for the public to see online is because I want to emphasize how important love is. Most people assume that love is just a feeling. But in reality, love is more than just a feeling. Love is sacrifice. Love is giving a piece of yourself that is sacred and letting it go for somebody else to enjoy. 1 Corinthians 13:4-7 says, Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. In other words, God is love.

If you ever have seen The Little House On The Prairie, by Laura Ingalls Wilder, you would know exactly what I am talking about. It speaks volumes of what actual love is. Adoption is also love. Believe it or not, adopting a child from a foreign country is unconditional love. Not only are you taking that child in but you are raising this child as your very own. This is what real unconditional love is. And that’s what I hope people learn from my adoption story.

Jena Heath: How old were you when you came home to the US?

Ivy Maldonado: Around three and a half. My mother had told me that I was found on the stepsof a government building in front of a government building around three months old in May.We don’t really know the detail about my abandonment. We’re thinking since I have some

things wrong with me that I was probably left in front of a hospital. Maybe somebody came andfound me. We are also thinking that my mother had died when I was older, like three monthsold.

Jena: What makes you think that?

Ivy: Because most babies are abandoned when they’re newborn. I was abandoned as an olderbaby.

Jena: I see. Three and half, do you have any memory at all of China?

Ivy: I’ll be honest. Having been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, my earliest memory is probably being up early, wee hours of the morning, crying and screaming or rocking at nightand being scared to sleep alone. I would rock like this in a weird way. Growing up, I wouldalways have a stuffed animal because I felt secure.

Jena: Do you remember some of things your dad was talking about, that when you first came home you were like, “Who is this guy? I’m very not interested in hanging’ around with him?”

Ivy: No, not at all.

Jena: I know you would like to do a birth parent search. Are you engaged in that right now?

Ivy: Yeah, I really want to do that. I feel like I could have hope. I can tell other Chinese adopteesthere is hope for girls that want to find answers and want to find theirself. It doesn’t meanyou’re ungrateful. It means that you want to search for self-discovery.

Jena: How would you do it? Have you researched ways to start to look?

Ivy: Sort of. I thought maybe I could put pictures on the internet or have somebody post pictures in Yiwu where I came from. I was told that I was Mongolian/Chinese. That’s why myface is very round and dark unlike most Han Chinese.

Jena: You told me when you decided you wanted to do “Our China Stories” that you’re hoping it’s in China. Is one of your hopes that your story might be seen in China by your birth parents?

Ivy: Yes. I definitely want to search for my birth parents. I’m a Christian. I believe in Jesus. All things are possible with God. Even if a baby is abandoned and you don’t have any clue, any paperwork or anything, you can still find a lost family member.

Jena: In a way the birth parent search is a kind of act of faith?

Ivy: Yeah. Also, I want to show that if you have faith in God, then anything can happen. If God’s will, will be done.

Jena: Tell me about some of the things you were talking about and your dad was talking about.You’ve had some struggles. Do you have a diagnosis of Asperger’s?

Ivy: Asperger’s syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Jena: When did these diagnoses start to come? When did you start to have this understanding about yourself?

Ivy: I don’t really know to be honest. When I first started to notice, first grade, it was that I wasn’t fitting in and making friends like normal people. That was difficult for me. I wanted to have friends so bad. People didn’t understand that I came out of an orphanage and I have some autistic tendencies.

Jena: What happened with other kids? Did they start to pick up on the fact that you were behaving differently?

Ivy: They would pick on the fact that I would behave differently. I would do awkward, quirky things like pick my nose. I wouldn’t brush my hair. I would make noises with things. People would be like, “What is wrong with her? Why is she acting like that?” They didn’t understand.

My mom knew that there was something going on. The teachers didn’t have any understanding. It was a public school with normal kids. They expected me to act like everyone else and be still for eight hours in a classroom. It was difficult. As I got older, they homeschooled me. They put me in charter school so I’d fit in. It didn’t work. Making friends was very difficult. I found the only way I could make friends was through other kids that have autism or Asperger’s.

Jena: Have you made some good friends that way?

Ivy: Yeah. I do have a friend that was diagnosed with Asperger’s, have some of the same symptoms. She’s grown up now. She works. She has a boyfriend, all that.

Jena: Is she distracted with her boyfriend at the moment?

Ivy: Yeah. She works. She goes to school. I found that literally if you connect with other people with the same disability, it’ll be easier.

Jena: Your dad was saying that there had been a period where you and he had some difficulty. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

Ivy: Sure. Most fathers and daughters connect normally. I don’t connect because of my disability. Also, I’m very defiant. I like things my way. I’m very determined. If I want something done, I’ll have it done. If I want something to go my way, I’ll be consistent. My dad’s just as stubborn as I am.

Jena: You guys would butt heads?

Ivy: Yeah, about little things like what clothes I was allowed to wear, what music I was allowed to listen to, what games I was allowed to play, whatever friends I had. I saw the world so much differently. All I saw was my dad giving me rules and structures and all these things that he

wanted me to follow. My dad saw somebody was who rebellious. I wanted to be like a normal teen. At the time, we also know that I was autistic too.

Jena: Do you think your dad was worried or afraid that in some way the autism and the defiance might lead you into situations that weren’t good for you? Maybe that’s the way that he was reacting out of a kind of fear?

Ivy: Yeah. I’m very vulnerable and gullible. I tend to believe what people say or people think. I had somebody told me that I looked retarded. I honestly believed them. My self-esteem suffered for it. If you want friends and you’re have a disability and it’s hard, connect with other people that have disabilities. Go into groups. Have support groups. That helps a lot.

Jena: Have you gotten to know other Chinese adoptees? You mentioned FCC.

Ivy: Families with Children from China, Adoptee, they’re putting on a service trip to China. It’s called Adoptees Giving Back – Orphanage Service Trip. They also do conferences in other states where all the Chinese adoptees get together and they bond. I actually met one girl, Nina, who was adopted from my orphanage, Yiwu Social Welfare Institute. She had gone to several trips, Adoptees Giving Back-Orphanage Service Trips.

Jena: Is that through Adopteen?

Ivy: Yeah. They have scholarships. They have fundraising. They have everything you can think of. It’s really good because you not only connect with other girls, but you go back to China. You get to help sponsor. You get to volunteer and help these other orphans in China where we’re at. It’s a link back to my past. That’s really important for me. I do want to go, but I don’t have the money.

Jena: That’s a goal that maybe at some point you could make an Adopteen trip like that. In the meantime it sounds like, is a lot of your networking that you’re doing on social media, through Facebook, reaching out into the communities that way?

Ivy: Yeah. I want to raise awareness and advocate for orphans in China and the one-child policy and all that. I want to show that there’s hope and make a difference in the community. It’s definitely a goal. I definitely want to go to the Adoptees Giving Back – Orphanage Service Trip as soon as I get the money saved up.

Jena: What are doing now? Do you live here? Do you live in your own place?

Ivy: I live in a place. It’s a cross between a group home and a family. It’s through Independent Options Adult Family Home Agency. It’s for adults with disabilities. It’s through San Diego Regional Center for Developmental Delays. I go to a day program for disabled adults. It’s called Easterseals Disability Services. I don’t know if you know about — Easterseals is actually worldwide. It helps people with disabilities be out in the community, work, have all the rights, all that stuff. My Easterseals is a national city. I go with a job coach and three other clients that

are also disabled to volunteer in certain areas in San Diego. We volunteer at the Humane Society. We volunteer at the Veteran’s Village. We volunteer at the garden. We volunteer everywhere.

Jena: That sounds really cool, actually. Do you like where you live?

Ivy: I do. It’s a Filipino family with two kids. There’s another client with a disability who lives there. It can get pretty chaotic.

Jena: How?

Ivy: They have a three-year-old daughter. They have a ten-year-old son.

Jena: It sounds like you’ve found a good living situation in which you have quite a bit of independence.

Ivy: It helps me be independent. At the same time I have someone guiding me, making sure I’m making the right choices, doing my laundry, making sure that generally I’m taking care of myself, seeing my psychiatrist, all that stuff. For some people, group homes can be too much. For some people, living under their own might be too much. This might be perfect ideal for people that want to go and be independent but have also some special needs.

Jena: Does your psychiatrist help in terms of helping you moderate your behavior? Do you take some medicine?

Ivy: I take sixty milligrams of Prozac. I’m on birth control.

Jena: That’s good. Those are both good things to be on. Do you think that Prozac helps you moderate your behavior a bit?

Ivy: I think so, in a way. What helps me most is knowing that there’s hope. I have goals out there. I’m going to work. I’m going to go to school soon. I’m going to be able to make it in the world. I’m going to be somebody. I’m going to be an active member of society. I’m not going to just sit around and do nothing.

Jena: I have the feeling that is definitely true. I don’t see you sitting around and doing nothing. Do you see yourself sitting around and doing nothing?

Ivy: Sometimes.

Jena: Really? It seems very unlikely to me. What are your goals? What do you think about I want to do? If you chose a profession, when you think five or ten years ahead if you ever do, what would you like it to look like?

Ivy: I would most definitely like to volunteer for Adopteen and go on the AGBOST trips, the Adoptees Giving Back – Orphanage Services Trips to help. I would also like to be an advocate and advocate for orphans in China. I want to serve in Chinese orphanages. I want to sponsor an

orphan in China.

Jena: Tell me a little bit about your faith. Your religious faiths seems to me to be very important.

Ivy: It’s not a religious faith. It’s actually a relationship with Jesus Christ. If you have Jesus in your heart, then everything’s going to go okay. There are going to be some tough times. Just hold onto Jesus. He’ll make your path straight.

Jena: This makes you feel more certain about that things are going to work out?

Ivy: I know God’s out there and God’s real. If God wasn’t out there, I wouldn’t be alive. I’d be dead in China somewhere. I’m lucky to be in America and have education, a family, support systems for my disability, everything. If I was in China, I wouldn’t have any food. I wouldn’t have

any education. I would be in an orphanage just sittin’ there, or I’d be out in the street beggin’ for food. Having a disability, they probably would lock me up in an institution.

Jena: What do you want to talk about most with this interview? What have I not asked you that you would really like to address?

Ivy: No matter what color skin you have, what race you are, what’s your personality, what’s your income, what’s your education, all that, you can still be a family. I have two black cousins that are twins. I have a brother who’s half-white who’s half-Puerto Rican. I have three little cousins that are two, three years old. They don’t look anything like me. I still love them. They’re still my family. Love makes a family, not blood.

Jena: You have a very diverse family?

Ivy: Yes, I do.

Jena: Your brother Eli, how old is he now? Thirty-one?

Ivy: He turns thirty-one in May, May 16th. His real name is Carlito Elias Maldonado Jr. III.

Jena: How do you guys get along?

Ivy: When I was younger, I didn’t like him because he was always in and out. He was always going out partying with his friends like a normal teenager. Right now as I got older, I have been able to see things. I’ve been able to realize that when my parents do die, I am going to have to

hold onto my brother and rely on him for things.

Jena: Does he understand that? Do you think he thinks of it that way too, that he’ll always back up your parents?

Ivy: I don’t really know. He’s had a very different experience in life. He has ten years of drug and alcohol abuse. He’s recovering for that, doing well. He’s a Christian. He sees the world as unfair. I agree with that. I have that in common. He also likes different kinds of music and different kinds of people. He’s more like the person that goes in the mountains and stuff. He’s like a nomad. My mom would always say he likes to be out and camping and mountains. His favorite music is that reggae stuff.

Jena: He’s a spiritual man, in his own way.

Ivy: What is that called? What is the name of the singer?

Jena: Bob Marely.

Ivy: Yeah. Bob Marely. He likes Bob Marley. He likes all that kind of stuff.

Jena: How ‘bout you? Do you like Bob Marely?

Ivy: He’s okay.

Jena: What kind of music do you like?

Ivy: I don’t know.

Jena: What do you like to do, things that you like to do? Do you like to go to the movies? Do you like to go shopping? If we weren’t here, what would you be doing right now?

Ivy: I’d probably be connecting with other Chinese adoptees over the internet, video chatting to figure out ways how I can help other orphans in China. There are three girls that are dying of cancer. They all were adopted from China. I’m praying for them.

Jena: This is really the center of what you’re thinking about right now.

Ivy: I’m really passionate about orphans in China because I was an orphan myself. I really want to do as a career is help orphans in China.

Jena: Is there anything I haven’t asked that you would like to address before I talk to your mom for a bit?

Ivy: I just want to raise awareness about equality in America and freedom. Everybody should be treated equally regardless of disability, race, regardless of education, income.

Jena: That’s a great message. I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

Ivy: Also, I want to make it clear that unconditional love, if you have unconditional love and God in your heart, then anything’s possible.

Adoptive Mother Carmelle Maldonado of Ivy

Feb 12, 2019

Carmelle Maldonado: We had a son. We call him a bio-son. I was more concerned about what if I have two children, one’s adopted and one’s bio? Am I going to love them both the same? I would not be to able to live with myself if there was some partiality. A child would know. I had a really hard time thinking about whether that was going to work or not. I loved my son dearly.

I thought, “How can I love someone else like that?” We did spend time praying about it. I spent a lot of time praying about it before we decided. The fact that my husband was so for it was good. When we first got married, we wanted five children. That was the number. He was from a

big family. I had a normal, middle-class family size. We liked that. Eli was about ten. He’s going to be retiring soon, my husband was. We either need to do it now, start adopting, we’re both getting older. We got the information, prayed about it, and decided that’s what we’ll do.

Over the course of the year, it took us a little over a year, I felt more and more sure that this was the right thing to do. Then through the process, I also got confirmation. God gave me confirmation that this is the particular girl, not just any girl. I don’t think he cares. We need to take the orphans and take care of them. I think he, for obvious reasons later, it helped me. That encouraged Carlos too, that we did get this particular girl with these particular issues, just like if we’d birthed her, you never know what you’re going to get when you have a child. That’s just the way it is. It worked out. The message that we got before we got her was enough to tell us

that yes, we’re going to do it. It’s going to be okay. We actually thought about going back and getting more. We thought, “We need a couple more girls, sisters. We need our five.” She was just going into the first grade. She had graduated out of her special needs classes, her speech therapy. She was doing well speaking, and getting the language down, and occupational therapy. They put her into a regular class and said she’s good to go.

Of course I’m like, “Yay! Now let’s go get a couple more. [laughs] We got this one going. Let’s go.” We talked about that. Over the course of that next year we realized she really wasn’t ready for me to take my attention from her onto anybody else. As she got older, it actually got a little harder. Getting older and getting out of the box more and being able to get out of the box more, it was a lot more difficult.

Jena Heath: She was three and a half when she came home. It sounds like it was fairly soon that you realized you needed to address certain issues then. Before we go there because I want to make sure I understand, how old were you both when you adopted, both you and Carlos?

Carmelle: I was forty-one, forty-two. He’s two and half years younger. He was a little bit younger. We were early forties by the time we got moved. We retired from the Navy with her and our son and came to Alabama where my parents were and decided to settle there a little while and get comfortable. We knew we’d have problems because she was older. We didn’t expect it to be easy. We knew that. With a small family like we had, we didn’t think we’d have a lot of problems. We had a good medical with the military. We didn’t think that’d be a problem.

Jena: Was she special needs?

Carmelle: No.

Jena: She wasn’t on the waiting child list?

Carmelle: No. The first two, three years as I tried to get her into preschool, that first year out when we were back and going forward up through first grade, I felt like she just needed to get settled in her body and her surroundings and her new world, and that it was going to take her

two or three years at least. If she was behind in everything, that’s fine. That’s to be expected. I wasn’t concerned. Teachers and other parents would make comments about it and show concern. My mother was concerned. I was like, “Do we know what to expect from a child that’s

been in an orphanage, especially a very difficult situation?” This is early nineties. We don’t know what is going to come out of this. We weren’t surprised at all with her issues then. We were surprised, though, as she got older and it got more difficult. I thought it would get easier.

She would get settled. She would get more comfortable. It didn’t. It got harder.

Jena: What were her first issues? What did you first see?

Carmelle: Sitting. She couldn’t sit still. She would rock at night, which wouldn’t normally be a problem. There were a lot of children that were doing this kind of behavior, the rocking. There were some sensory issues that she had right away about movement. Actually, she wasn’t walking really well. We felt like maybe she was constrained a lot. That was going to be an issue, working through that. She wasn’t walking well. She could not sit and look at what was going on even for ten minutes in a desk at a preschool, for example. She lasted about three days. It was not happening. It was her movement, inability to sit still, very distracted over everything. That was the first part.

On the other hand, she was also very easy to get along with. She wasn’t smiling a lot at first. It got to where she did a lot of giggling, very silly. She had a lot of fun. Me and her had a lot of fun when she little. I enjoyed showing her everything like it was for the first time. The first couple of

years we were just havin’ a ball. Everybody else was havin’ the problems, not us. [laughs] My husband didn’t either. By the time she was six, seven years old, they wrestled around and be silly and goofy. He’d make her laugh and scream. They had a great time. He didn’t mention that.

They did. They had a great relationship.

Her and her brother had a great relationship. They used to tease each other. Actually, I’ll take that back. She didn’t tease well. Him and his friends would come. They enjoyed her because she was so out of the box. She was a little different. She was a little quirky. She wasn’t whiny. She

didn’t cry over it. She was a real tough, little, have-fun, and curious about everything. One of our problems was she wasn’t afraid of anything. She was afraid, but not of normal things that most little girls were afraid of. I had to be extra vigilant to watch her in that way. She would be fearful over, like she said, at night, being by herself.

Jena: Was she not afraid of other people? She’d walk up to a stranger or she’d charge into –?

Carmelle: — She could. She would. She’d always know where I was. I was her lifeboat. I was her bread and butter. She knew that from probably the time we went from the lobby when they handed her to me to the hotel room. We shut that door. That was it. She didn’t scream when —

I will correct my husband on that — she didn’t say anything. She just looked at me. Neither one of us knew what to do at that point. She didn’t until we got back into the hotel room and shut the door. She realized she was going to be — that scared her. I sat with her all night. She only cried a couple of times that night. She sat with me and slept on me in a chair or in the bed sitting up just because I didn’t want to move. That was it. The next morning she woke up, and it was like she’d been with us, understood we’re going. Let’s go. You’re my bread and butter. She really enjoyed my son. They got along, played very well together. I couldn’t leave her with

Carlos. [laughs] He had a beard.

Jena: He looked like someone she’d never seen before.

Carmelle: Maybe she hadn’t been around men. That didn’t surprise us.

Jena: You get through this initial phase. She gets through the preschool phase, which at first is rocky. It sounds like you get through there. You figure around kindergarten, we’re out of the woods. We’ve had our initial couple of years of adjustment. Now, the arrow is going to go up, up, up. Then what happens?

Carmelle: We get her into kindergarten. Within a couple of days they call and say, “This is public school.” She was already taking some language, speech, English help at that time. They had an early start program. We were there. We get her in. They end up keeping her out of her class

more of the day and in special classes for speech and occupational therapy and all that. She would only sit in a classroom maybe an hour the whole time. This was a half-day program for the first year of kindergarten. She really didn’t do much kindergarten. They repeated, they wanted her to repeat. She repeated it the next year doing the same things out of the class for most of the time, just maybe an hour. That was okay.

She went into first grade into a different classroom, a little bit more in the classroom, a little bit less out of the class. Still having difficulty, getting into trouble every day. She’d come home and be able to tell me, “I didn’t get recess.” That was every day. I would go to the school. We’d have

more consults. We pulled her out more, giving everybody a break. They said, “Second grade, she’s clean. No more special anything.” That was probably her hardest year. That was the year when she’s eight years old, nine years old maybe. She was a year older than everybody else. “I’m different. Nobody talks to me. Why did they talk at lunch?” She never got a recess. She’d sit on the black pavement because she wasn’t good during class.

I’d be in the school every month talkin’ with the teacher. I said, “This is it.” She’d come home in tears. I’d say, “This is it. We’re going to have to do something else. We can’t do this public school anymore.” They helped her. They helped her with many, many things. They felt they were done. This wasn’t an option. It wasn’t working. I said, “We’ll finish second grade. Then we’re going to try some homeschool for a little while.” I thought, still, we got to give her some time. Give her some time. The emotional part was the hardest. How can she sit and study and do what she’s supposed to do when all she wants to do is make connections with kids, and

frustrated, and getting into trouble? She can’t sit. We did that. We let her finish second grade and pulled her out. We homeschooled. We moved here. We homeschooled for three years. The last year was here. She was doing very well. I was feeling like she was doing very well. She was

doing, in the fifth grade, pre-algebra, very smart. Big problems with her reading — we knew that — with her ability to understand what she was reading. She couldn’t read more than a paragraph without having difficulty understanding if she had to carry that information into the next paragraph. We focused mostly on the classes like math and art and writing and English skills. The reading, I helped her a lot with.

By the end of fifth grade — this was three years home school — she wanted to go. She said, “I don’t have any friends.” I had her in gymnastics. I had her in church. She was over in church two or three times a week and groups. I knew why she wasn’t having friends. She was not able to.

She didn’t have any social skills. The last year that she was in fifth grade I had read a book on Asperger’s. I’d read lots of books people were giving me. I read this one and in the first introduction, the first page, I said, “Oh, my gosh. That’s Ivy. She’s got Asperger’s.” I read it my husband. I said, “Does this sound like Ivy?” It was a little story about a boy talkin’ to the

postman. He goes, “Yes.” I said, “That’s what is wrong with her. That’s the deal here.” When we got here and I was homeschooling her in the fifth grade, I knew what was wrong. I knew why she wasn’t makin’ friends.

We had been to a clinic in Birmingham that helped us, an adoption clinic that put me onto some more things to be thinking about. Having said that, they said, “You’re going to California. You’re going to get lots of help. When you get out there, get a social worker or get a psychologist. Get somebody to help you sort out what you’re going to need to do.” We did that. Then into fifth grade she says, “I don’t want to do this anymore. I want to go to public school. I want to make friends. You’re not helping me make friends.” I said okay. I called ten different people. I ended up getting somebody really smart on the phone. They said if you want to get her help, you have to get her diagnosed. The only way to get her diagnosed is to get her into public school. I’d already taken her over the public school. They tested her and said, “No, she’s not autistic.” I told him. He said, “No. You have to get her in school. Get her in school.”

Jena: Enroll her. Then there’s an interest in diagnosing her.

Carmelle: They have to figure out if that’s not the problem, what’s going on? He said, “They will help you.” I was in my ropes too. If she wasn’t going to listen to me anymore and sit and do her work, I had to find something. That’s where it all started. I started there. I started getting

connected with people who told me, “Go to this clinic. Try this doctor. Go this route.” Long story, many different counselors and doctors, we ended up in the Amen Clinic up in LA. One of our counselors said, “You need to go up there.” Actually what it was, was we went to a psychologist up there. She was trained in the adoption issue, attachment. She was a specialist.

There were only two in this area. I took her. I said, “I need to know if that’s part of our issue.” I already knew she was Asperger’s. I didn’t even tell her that. I just said, “I just need to know if it’s attachment.”

She spent about ten minutes with her, said, “No. That’s not what’s going on. There’s something else going on. You need to get a picture of her brain.” She suggested the Amen Clinic. I took her there. They did a picture of her brain. They came back. They didn’t say autism. They said brain

injury. There’s brain injury. I ended up with two brain specialists — one was a psychologist and one was a psychiatrist — here to say, “This is what the pictures say.” They said, “We don’t pay attention to what the Amen Clinic says.” I didn’t know what they were really referring to. They both said, “No. She’s got autism.”

Jena: What’s the Amen Clinic? How do you spell it?

Carmelle: A-M-E-N. Dr. Amen. They do some, what I would say, out of the box, not quite mainstream, and not necessarily accepted by everyone. They could tell me what was going on in her brain. Then from there, I also went to a psychologist doing the neurofeedback. One of my other friends, her husband had Parkinson’s. He said that really helped him. I got on the track of this, going this direction. In the meantime, they’re in school. We put her in public school, another fun story. The neurofeedback helped. They said, “We can see.” When you put the nodes on and you see the brainwaves, you can see the brainwave. There’s damage here. There’s damage up here. Then I took her to a neuro-doctor here who looked at that and talked about the history. He said, “You know, it’s possible that it’s institutional autism.”

I said, “Okay. That makes sense,” maybe that combined with her brain injury. When I went to the school and the school psychologist when I put her into school, put her into junior high. It was sixth grade. She was going into junior high, really scary. They put her into seventh grade. She had skipped a grade. She said, “I think she’ll do better if she’s with the kids

her age. That’s a good thing.” I said, “She can do the work, maybe. She’s smart. She can do the work.” The psychologist there, the speech therapist, worked with her and said, “It doesn’t make sense. It’s two pieces, the autism and the brain injury. She doesn’t fit in either, but she fits in both when you put them together.” That was my confirmation. Now that we know what we’re dealing with, we can see about helping her the most, what school she goes to or what classes she takes. What’s the kind of support she needs to get? Not because I already knew, I already

knew she was this Asperger, wonderful, quirky, says everything you want to say but can’t. That’s the steps on how we really figured out what was going on with her.

Jena: These two other doctors who reviewed the Amen thing who are more traditionally neurological doctors say, “No. We don’t listen to them.” You believe that there is a physical injury or some kind of injury to the brain and that she’s also on the spectrum with Asperger’s.

Carmelle: Yes. I had two different psychologists tell me the same thing doing the neurofeedback. One of them worked with brain-injured for depression. She knew what brain injury looked like on her monitor. I knew. That amazes me. I have a friend who has a son who’s had a brain injury. Very similar, sometimes with social skills too, not able to understand. For

me, it was quite a comfort to have everything all come together. She was about fourteen. We knew. Of course, that’s when everything fell apart because she was going through her puberty and her hormones. She wanted a boyfriend. She wanted girlfriends. I’m so glad we’re done with

that. [laughs]

Jena: Did she go through high school and graduate from high school?

Carmelle: She did. She actually took her CAHSEE exam in the tenth grade and passed it. That is what you have to pass to graduate from high school here. By the time you’re a senior, you have to have passed it. You have to take it once every year ‘til you pass it. She passed it in her tenth

grade. Then since she didn’t have anything else to do, they put her in the ED room. That’s where she sat for four years.

Jena: ED?

Carmelle: Emotional disturbed. That’s where she wanted to be, was a public school. We went into a charter school. It was mostly homeschool. She did go two days a week. She was doing okay. She was holding her own. That didn’t work well. She wanted to go back to public school. I

put her back into public school. I pulled her out one more time to try charter school again. She’ll tell you now, “I wish I would’ve stayed there.” She kept thinkin’ it’s going to be different. She’s

going to get into this school over here, the high school with all the kids. It’s going to be different there. It wasn’t.

Jena: Now, she’s living in a group home situation. She sounds happy there. Carlos indicated that she may have a job soon? She is looking for jobs?

Carmelle: She’s pushing. You know Ivy, she’s pushing. This is what she wants. She’s been with the program going on her fifth year. She’s doing very well. We’re thinking if we edge them on and push them a little bit to try to get her into something — they tried to get her a job when she

first got into the program. She wasn’t ready. She did not even want to say that she was disabled. She wouldn’t say it. “No, I’m not. I’m not disabled.” She couldn’t. It took her about three years in a program to be able to accept that she has a disability. It’s been a godsend. We felt like until she gets to where she can say that, she’s not going to improve. She’s not going to work on these issues. She needs to accept who she is and whatever disabilities — we all have them — and work with it. She’s getting now where she can obviously say it. That was only about two years ago that she could even say that. We’re excited.

With the autism type area, you grow slower, mature slower. They say by the time they’re in their thirties they get it. We see that. We see her maturing. We see her progressing. We see her making sometimes some very wonderfully mature conclusions about the world. We love that.

That’s good. The brain injury holds her back a little bit. She’s in there. Sometimes we see her brilliantly. Sometimes the emotions, like any woman, they get in the way. As she gets older, and gets more mature, and gets to love herself more, and accept, and start looking forward instead

of looking back — she’s still stuck in the back. That’s part of the nature of her disability.

Jena: What’s the name of the program she’s in? You said she’s in a program. Is that the group home?

Carmelle: Yes. Her program is called Independent Options. They have many here that you can get into. Her overseer is regional, which is a statewide private-funded — they may get some funds from the government. It’s a nonprofit that helps fund the programs that these kids are in.

She has a social worker through this regional so that when we’re not in the picture anymore she will always have a social worker there looking at her day program, looking at where she’s living, trying to help her meet her most independent way that she can to live. We think that it was real blessing to come here for her. She has it all here, as much as she wants. She can go as far as she wants in this program.

Jena: You mentioned her looking forward as she matures and accepts and begins to look forward. It made me wonder what you think of her intensity about searching for birth parents. That’s backward, in a way. I wonder how that feels for you, not just in adoption terms in terms of how that feels as an adoptive mom, but also in the full context of the things we’ve been

talking about Ivy.

Carmelle: Part of her search for her birth parents — it didn’t start ‘til about five years ago. Like she said, she’s OCD. That’s good that she’ll say that. Her love for China, I think it’s a real love for her birth parents. I don’t know where she got it. She has it. She wants to know them. I think it’s

very healthy. For her, she’s a little overboard. That’s all she talks about. That’s her main goal right now. It is backwards. I feel like if she could concentrate more on what she can do for herself, for her future, rather than what’s happened in the past, I think that’s holding her back

because it consumes her. That’s her.

I understand most adoptees want to know. Maybe they can’t express it. Maybe they’re afraid to express it. It’s a very natural desire for people to know who their birth parents are. We encouraged it when she was younger. We thought, “Yes.” We encouraged her. The only thing that I would get upset with her is her misuse of where she may have been found or the circumstances. If we don’t know, then we want to put a good light on it. We don’t want to talk badly about it. I told her, “It’s disrespectful.” She’s getting better at speaking better about her situation. Maybe we don’t know for sure, everything. We do know she’s from Yiwu because we saw that video. We can trust what we she knows. That’s all we can do.

Jena: How was she characterizing the circumstances of where she was left that made you uncomfortable? What was her take?

Carmelle: She’s angry at being left. She feels abandoned. She feels that. I think that if she could find her birth parents and hug them and they could hug her back, it would all disappear so easy. It would be so easy to disappear. That may not ever happen. It may happen badly. If anybody

can find their birth parents, I’m telling you, it will be her. I think that’s she angry. That needs to go away first. I don’t think that’s a healthy perspective. You need to appreciate that they were there, that they took her to a safe place. She shouldn’t dwell on the bad part of it. It’s done. Be

thankful they’re so smart to have put her in a safe place.

Jena: Has she ever articulated whether part of her anger is that she connects the difficulty she’s had with the fact of being abandoned? I’m wondering if she’s ever said anything like that.

Carmelle: No. She has just in the past year probably talked about, “If I had a baby, would my baby have this disability?” I would say, “I don’t know. Granted, if it is actually autism that we think it is, maybe your mom or dad or an uncle or an aunt had it. That’s a possibility.” Very unusual to me — I still have a hard time understanding this — she would look in the mirror and say, “I live here. My birth parents would never recognize me. I look American.” I say, “No, honey. You don’t look American. You look in the mirror, you look just like your mother. I’m sure.” The bend on the toes, I say, “You’ve got these funny bent toes. I bet your mother has the

same funny bent toes. Just go to China and look at everybody’s toes. There she is.” We’ve had some very funny conversations about her birth parents. I would imagine, like most other adoptive moms, that you want your child to be at peace. This would give her such peace. I pray for her. I tell her, “If God wants you to find them, you’ll find them. If you don’t let up on him…” [laughs] You never know, especially her. Use it to your advantage.

Jena: The way I want to wrap this up is to ask you about where you are now, the way I did Carlos. You adopted this child. You had, like all of us I’m sure, a whole idea and set of emotions about what that would be like. Am I wrong in saying that it turned out to be a different experience than the way you had imagined it? How is that for you?

Carmelle: I’ve always felt this way. I asked God that when I get this child if I can just love her like I love my son. That’s all I need to do, just be able to love her. That is infinitely the best. That has been what’s driven me to such lengths to protect her, to try and get her help, to go out and

make friends for her, all the things that a mom does for her kid. Mostly I just want her to have a peace and acceptance about herself. When I first started off, that’s all I wanted from my end. I wanted for her to have a good life here. If we could go back and get five more, then so be it. Let’s go back and get five more, just to give them an opportunity for a good life. Being in an orphanage is not a good — for anyone, here or there — families are really important. Like Carlos said, we would do it again. Where else would we be if we didn’t have her and the struggles? We would be golfing. [laughs] I can’t see myself golfing. We’re still fighting for her. We’re still

advocating for her. I guess that’s going to be the way it is until we go.

Jena: We’re ending where we started. You told me your concern when you were deciding whether to adopt was could you love Ivy, an adopted child, as much as your son. I’m assuming that you discovered the answer. What’s the answer?

Carmelle: The answer is you can. I have always told other parents considering adoption — I know other mothers are probably just as concerned when they have their own bio-children. Yes, absolutely you can. Sometimes you love them more. You’re more protective and more

concerned. With my son, I always looked at him and said, “You had it all. You don’t need anything else.” That’s part of the family dynamics is the relationships. Yes. I’ve told other parents this. Don’t ever worry about that. That’s not going to happen.

See link: